Testing The Limits Of Your Language

How debating a native speaker uncovered gaps in my language abilities

The Creative Mind

One day, around 24 years old, I sat down to attempt meditation, or at the very least, to quiet my mind. A few people had told me to focus on my breath and try not to think about anything else.

I curled up in the corner of my bed, legs folded, hands on my knees, shoulders relaxed. I closed my eyes and tried to stay still for a few moments. Almost immediately, my thoughts began to appear.

It was like watching cable TV flooded with advertisements. Thoughts flashed in and out at high speed, in a never-ending fashion. I was genuinely surprised by the volume of thoughts I was experiencing.

Was this what I did daily without noticing?

Even more interesting was the nature of the thoughts themselves. Some of them felt like they had never reached my consciousness, just fragments of things I had absorbed over time, recombined in strange ways.

Our brains absorb vast amounts of information, much of it unconsciously, and then create new experiences by mixing and matching. And Why wouldn’t it be? Memories aren’t stored neatly, so it makes sense that new ideas emerge this way.

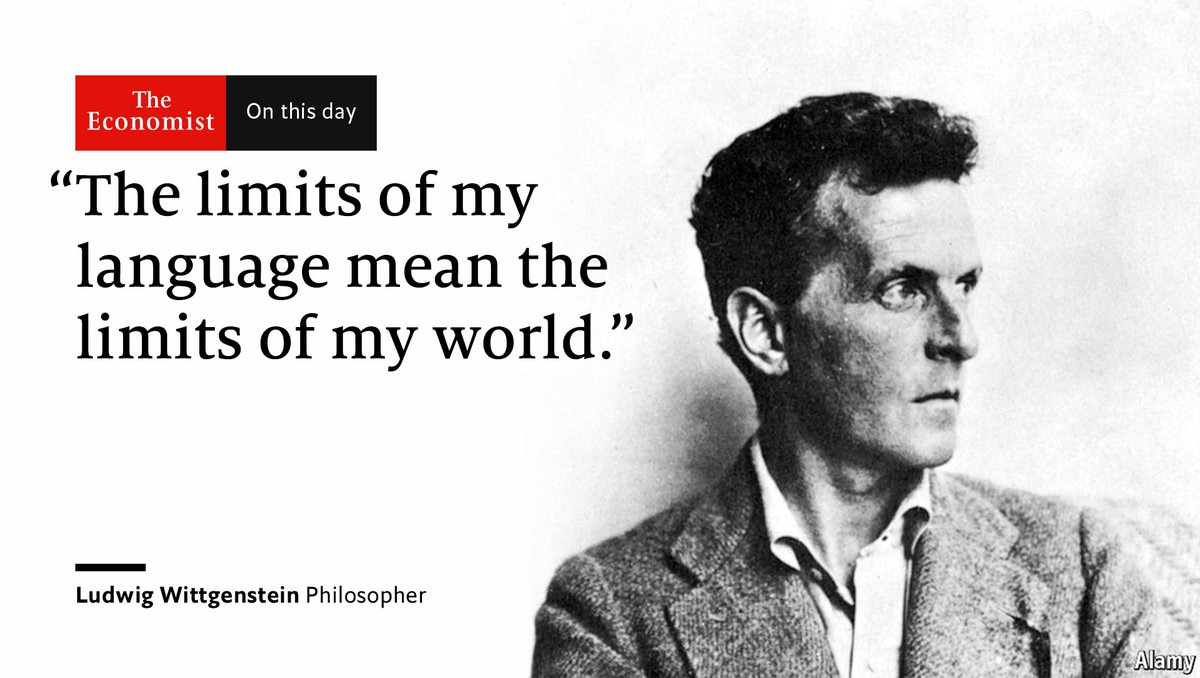

I began to believe that in our minds, there exists a universe of never ending concepts constantly being created (and destroyed?). And Language is the tool we use to translate these thoughts into something that can be understood by others.

Language Ocean and Seas

In order to use these tools, they must first be cultivated. Through countless hours of comprehensible input, we build a language ocean, rich with vocabulary, patterns, and associated meaning. However, we never actively access the entire ocean as native speakers.

One source claims that our active vocabulary is approximately 5,000 words while our passive vocabulary could be up to 40,000 words. This is a mere 12.5%.

For adult learners, acquiring a second language is different. We cannot cultivate an ocean but a language sea. The volume of this second language will never match the first, given the circumstances of life. However, we found a method to produce similar results of that of native speakers.

The Pareto principle applies: roughly 80% of our daily language comes from 20% of our language ocean. Therefore, focusing on that 20% of what a native speaker uses daily first gives the impression of proficiency in the language, and allows for full integration into society.

Adults learners start at zero like babies in their target language, but our progress is faster than that of a child. We do not require the same amount of cultivation time to be able to communicate in a new language. In fact, we can start speaking from Day 1.

A B1-level adult learner has the expressive capabilities of a 7–10 year-old native speaker: able to discuss familiar topics, narrate experiences, and express opinions despite a smaller vocabulary. I consider myself B2 in French, able to handle more complex and abstract topics, similar to a 12–16-year-old adolescent reasoning about the world.

The Encounter

In October, I thought I had reached a solid level in French, tenses flowing almost automagically, good level of vocabulary, pesky grammar rules internalized. I was ready for my toughest (and favourite) language sparring partner: a French girl named Lynn.

We met up at a café one Saturday afternoon, and we debated several topics. The results: she thoroughly kicked my butt.

Apparently I misunderstood contexts, mispronounced words, hesitated over past tenses, lacked important vocabulary, and even struggled to explain concepts I could barely articulate in English. I felt like a 16-year-old teenage arguing against a PhD interlocutor. The power difference was obvious. At this point, I realized that not even 50% of my language sea was accessible.

Before that encounter, I had spent days shadowing France Culture radio, drilling French past tenses, immersing myself in popular French series, and compiling a mountain of new expressions. All in preparation for a combat of linguistic prowess. Lynn is not someone to pull her punches. She danced around me with precise vocabulary and flawless argumentation. I caught her in only two mistakes (she was tired); the rest was perfect.

Takeaway

Input is important, as it develops our language potential. However, no matter how much we know, our ability to communicate depends on how much of it we can access. Forcing output with speaking and writing activities are required to broaden that access.

Facing a native speaker at higher levels exposes gaps and shows where our flaws reside. Immersion and challenge are essential for true growth. After all, truth is tested in action.

Thank you for reading!

You can see some of my older articles here.

Very nice, I liked the comparison with children of different ages, it illustrated very well what our expectations in foreign languages should be!

Have you two debated in English? I’m curious because you said you struggled to explain concepts you could barely articulate in English.