Language Output: Training Your Brain to Speak

How structured practice and real conversations shape fluent, accurate speech

I talk a lot about input. I encourage daily exposure, even just ten minutes per day, because input builds the foundation every language needs. Most of my languages are still in early development, so they need to develop a solid base. But lately, my attention has shifted to the other side of the process, the part many learners avoid because it feels uncomfortable and sometimes even humiliating.

Output.

The refining mechanism required for clear communication.

Natural Language Skills

Speaking and listening are the natural language abilities of the human species, and the ability to speak clearly and confidently is often treated as the true measure of Language proficiency.

A recent experience illustrated this sharply. After years of exchanging text messages with a Brazilian friend, In a hurry one day, she sent me a short voice note. The message sounded hesitant and choppy, and despite knowing her strong command of written English, for a moment, almost instinctively, I caught myself questioning her linguistic abilities. It became clear how quickly spoken output influences judgments of linguistic competence.

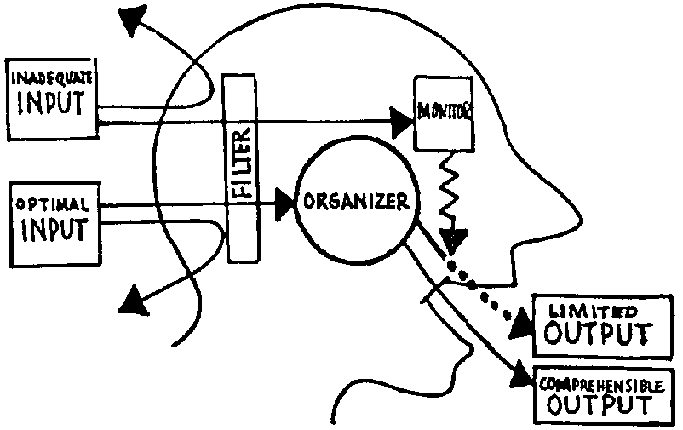

The Output Hypothesis

In the 1980s, Merrill Swain observed that in Canadian French immersion programs students would receive years of high-quality input, yet their spoken French remained full of grammatical errors and gaps. This finding led her to propose the Output Hypothesis

Swain argued that output is a key mechanism for developing linguistic competence. In her words, producing language “pushes learners to process language more deeply than they do in comprehension”. When we attempt to speak or write, we are required to retrieve forms, assemble structures, and select meanings actively. This active pressure changes the internal system in ways that input alone cannot.

Swain identified three central functions of output:

The Noticing/Triggering Function:

Output draws our attention to what we cannot yet do. As Swain wrote, producing language “may prompt noticing of a linguistic problem” (Swain, 1995). When our intended message meets our limited ability, the gap becomes visible. This noticing makes the brain receptive to the missing form the next time it appears in input.

The Hypothesis-Testing Function:

Every attempt at production is a small linguistic experiment. We assemble a structure and “test out” our emerging knowledge. Swain explains that learners use output to try out their current hypotheses about grammar and meaning, observing how well they work in real communication.

The Metalinguistic (Reflective) Function:

Writing or speaking encourages internal reflection about language which is what Swain called “metatalk.” We monitor our output, reformulate sentences, compare alternatives, and think consciously about form and meaning. This reflective loop deepens understanding.

Together, these processes refine the internal system in ways input cannot, but refinement is slow. Reaching high-level proficiency is especially difficult when living outside the linguistic community, where opportunities for spontaneous output are limited.

Refining Output

To accelerate accuracy while allowing fluency to develop naturally, a structured method becomes essential. Speaking ability often fluctuates due to inconsistent practice, and active vocabulary can even recede over time, which can be frustrating. Accuracy is especially difficult to build, given the complexity of grammar rules, exceptions, and the risk of negative transfer from native languages.

To address this, I use a refinement system that aligns closely with Swain’s Output Hypothesis. Alongside regular output methods such as speaking and writing, I use a method that I call the Mass Sentence Method, first described on the AJATT blog years ago and later integrated into Glossika’s language learning app.

The idea is simple: Internalize 10 Thousand Useful Sentences in the target language. Repeated exposure and production engrain these patterns automatically, reducing cognitive load and allowing fluent, accurate speech to emerge. This approach pushes the brain into a continuous refinement loop, combining structured practice with the active recall that drives lasting proficiency.

Conclusion

Viktoria Verde, PhD was right that we should speak until it hurts…however if we have a low pain tolerance then it’s starts hurting pretty fast. Internalizing a few sentences can help to increase that tolerance for pain and reduce frustration.

At the end of the day, we cannot get fluent in a language without speaking, and real conversations helps to fine-tune your inner language models. The Mass Sentence Method is just a structured way to accelerate this process. Also, remember, language learning is a journey and road to proficiency is not is a short-term project. As El Boletín said, even at a high level, mistakes are still evident.

Thank you for reading!

You can see some of my older articles here.

Though I was not familiar with the Mass Sentence Method, it seems that I have been using it naturally for years. As well as learning words in chunks rather than individually, I have been making flashcards and learning full sentences that I encounter during input. These were sentences that I found useful in my own situation, such as 'If I say anything strange or use the wrong grammar, please correct me!' or 'Gosh, it looks like my brain isn't working properly today... Sorry about that".

This approach has indeed helped me a lot during conversations with friends, and I feel much more confident overall. So my personal experience definitely aligns with what you wrote in that article. Thank you for sharing!

I wished I’d known about the Mass Sentence Method when I was studying languages! But it’s never too late. I will try it with Portuguese.

I’m sharing this with a friend who teaches English as a second language, she can share the MSM idea with her students.